The AI Licensing Gold Rush Is Built on Quicksand

Why the Current Model Is Broken according to People Inc’s Chief Innovation Officer

AI companies can process about 1,000 articles for $10 in compute tokens. For publishers, producing those same 1,000 articles costs $1 million, or $1,000 per long-form piece, after factoring in staffing and operational costs.

Dr Jonathan Roberts, Chief Innovation Officer at People.Inc. laid out this maths in a recent INMA webinar on content licensing. His conclusion: you can’t build a sustainable business model on a 100,000x cost disparity where one side pays nothing.

Roberts, whose background spans astrophysics and advertising models, has been working to solve the AI licensing problem from a position most publishers don’t occupy—he understands both the technical infrastructure AI companies need and the economic realities publishers face. His argument is straightforward: AI companies are strip-mining their own supply chain. Quality journalism requires serious investment. AI systems treat it as free. Something has to break.

He called it an “existential threat to the AI economy.” The numbers suggest he’s underselling the problem.

Why Quality Suddenly Matters

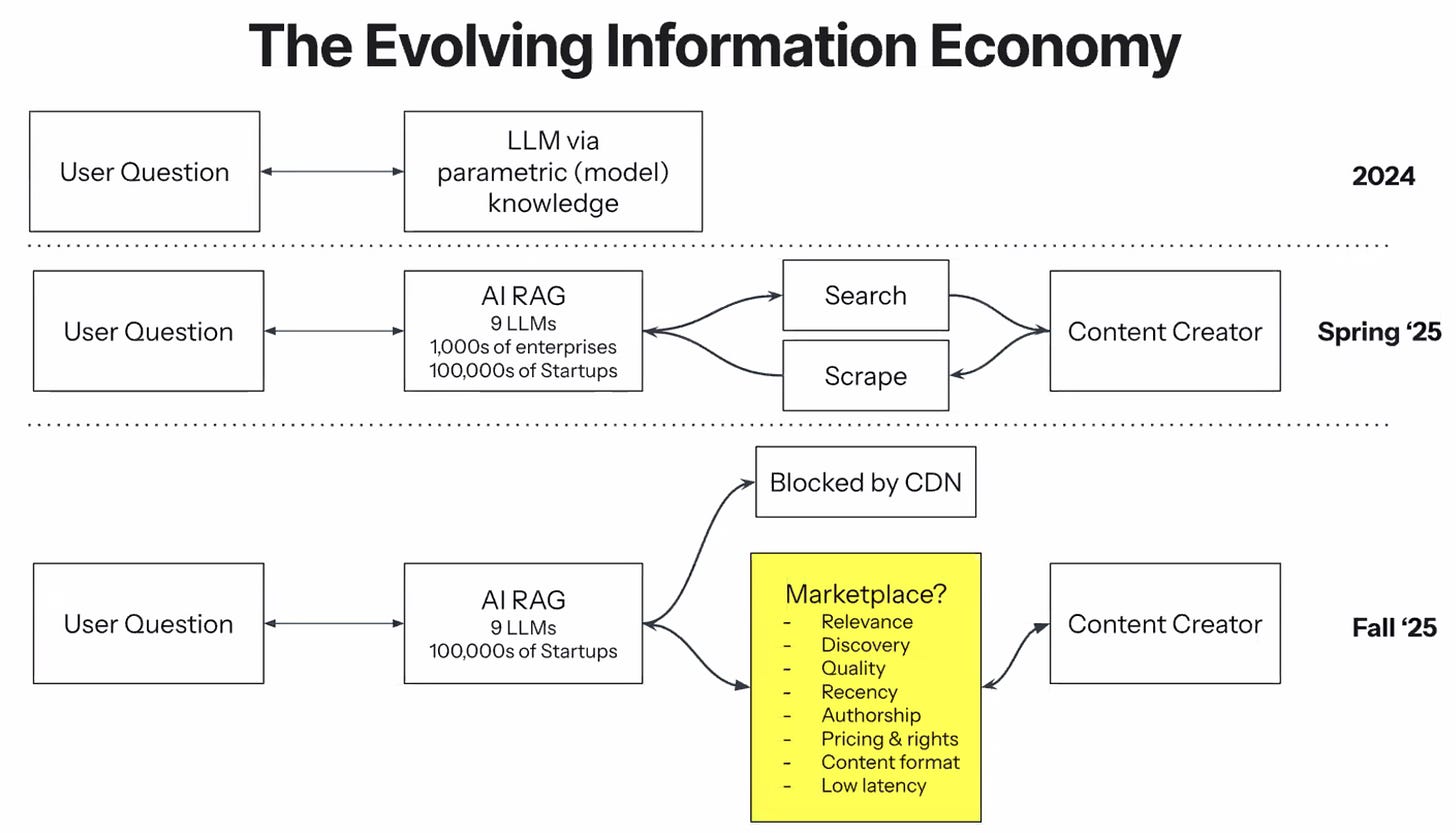

Roberts’ central thesis revolves around a shift most people have missed. Early AI models relied on volume—scrape everything, train on millions of documents, and let statistical patterns emerge. That worked when these systems were sophisticated autocomplete tools.

But models like DeepSeek demonstrated something crucial: when technical capabilities level out across competitors, accuracy and sourcing become your differentiators. You can have all the processing power in the world, but if your model hallucinates or provides unreliable information, users will go elsewhere.

This is where Roberts sees the leverage shifting to publishers. Media organisations produce vetted, fact-checked, expert content with clear provenance. In a market increasingly worried about misinformation, that’s not optional; it’s essential.

Yet most publishers still haven’t figured out how to extract value from this position. They’re either blocking AI crawlers entirely or signing vague partnership agreements that deliver tools and grants rather than actual revenue.

Building the Infrastructure That Doesn’t Exist

Roberts isn’t just diagnosing the problem—People.Inc is working on building the infrastructure to fix it. His vision for a functional market includes several components that barely exist today:

Clear provenance for every piece of content. Quality signals that distinguish expert analysis from random blog posts. Flexible pricing models tailored to the use case. Feedback loops that help content creators see the value of their work.

The challenge, as Roberts outlined, is that publishers need clear rights frameworks, fast retrieval systems, and structured data. AI companies need reliable access to verified information. Neither side can build this infrastructure alone.

Robert Whitehead, Digital Platform Initiative Lead at INMA, provided an overview that reinforced just how immature this market remains. Cash transactions are rare. The major players—OpenAI, Microsoft, Anthropic, Google, and Meta—are pursuing entirely different strategies with no emerging standard. Various organisations are working on protocols and frameworks, but everyone’s still making this up as they go.

The Agentic AI Urgency

Roberts emphasised why 2026 matters. The shift toward “agentic AI”—systems that take autonomous actions rather than just answering questions—makes the quality problem acute.

An AI agent booking a restaurant or making a purchase decision can’t rely on plausible-sounding nonsense. It needs accurate, verified data. As AI moves from answering questions to taking actions on behalf of users, the tolerance for hallucinations drops to zero.

Publishers with verified, expert content suddenly become vastly more valuable—if they can actually monetise it. This is the window Roberts sees for building a proper market, before AI companies figure out workarounds or publishers give away so much for free that they destroy their own negotiating position.

Why Roberts Is Pessimistic

Despite working on solutions, Roberts presented two scenarios and made clear which he considers more likely.

The optimistic scenario: both industries recognise they need each other and build the infrastructure to make the relationship work. AI gets reliable information, publishers get sustainable revenue, and everyone prospers.

The pessimistic scenario: we muddle through with defensive blocking and one-off deals while the fundamental economics remain broken. Publishers continue producing expensive content that AI companies consume for free. Information quality degrades. Trust in AI erodes. The whole thing collapses.

Based on what Roberts is seeing, we’re trending toward the second scenario. There’s plenty of activity—pilots, partnerships, press releases—but not much actual progress on the hard problems of rights, pricing, and scalability.

The challenge isn’t technical. Roberts is clear that the raw materials for a functional market exist. The challenge is coordination. Publishers are used to competing, not collaborating. AI companies are used to moving fast and breaking things, not negotiating complex licensing frameworks.

Getting both sides aligned on standards, protocols, and economic models requires industry-wide cooperation that historically doesn’t happen until after a crisis forces it.

The Narrowing Window

What worries Roberts—and should worry publishers—is timing. By the time publishers are organised enough to demand appropriate value, the AI industry may already have figured out how to work around them.

There are only so many high-quality information sources in the world, but there are also only so many years publishers can afford to give away their most valuable asset while waiting for a market to materialise.

Roberts emphasised that the decisions made in 2026 determine whether we’re building toward something sustainable or just delaying the inevitable. The fundamental question isn’t whether AI needs publishers—obviously it does, especially as quality becomes the differentiator.

The real question is whether publishers can extract appropriate value before they’ve destroyed their own negotiating position by giving away too much for free.

Why This Needed an Outsider’s View

Perhaps what’s most valuable about Roberts’ perspective is that he comes from outside the traditional media world. His background in astrophysics and advertising models means he understands the technical requirements AI companies have while also grasping the economic realities publishers face.

Sometimes you need someone who isn’t embedded in industry politics to point out that the emperor has no clothes. Roberts’ work at People.Inc is building the infrastructure that makes a functional licensing market possible—not just in theory, but in practice.

Whether publishers can get organised fast enough to use it is another question. Whether AI companies will participate in good faith remains an open question. But at least someone’s building the tools rather than just talking about the problem.

The question is whether anyone’s listening.