The Financial Times proves expensive journalism can work—sort of

Quality costs (and the FT isn't apologising)

Jon Slade, CEO of The Financial Times, Image © INMA

The Financial Times charges £600/year and thrives. Analysis of Jon Slade’s INMA webinar reveals why the model works—and why it won’t save most publishers

Jon Slade joined the Financial Times two decades ago without a grand plan. He was trying to work out how to make quality journalism pay. Twenty years later, the FT charges £600 a year for a premium subscription and has just blown past 3 million paying customers. On an INMA webinar, Slade—now Chief Executive—is answering questions from media executives in 37 countries, all asking the same thing: what’s the secret?

The answer, it turns out, is that there isn’t one—at least not one that travels well.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: the FT operates in a different universe to most publishers. Its readers are fund managers, Chief Executives, and lawyers who need the paper to do their jobs. Many expense their subscriptions. The journalism helps them make money, or at least avoid losing it. This is not a typical relationship between reader and newspaper.

Still, Slade is disarmingly frank about what’s worked, what hasn’t, and why the industry’s obsession with artificial intelligence might be missing the point entirely. Some of it is worth examining, even if you can’t replicate it.

Making expensive journalism more expensive

The FT’s commercial strategy rests on a single bet: truly distinctive journalism—the kind that’s “really quite expensive to produce” will always find buyers. Not millions of them, perhaps, but enough to sustain a business.

This isn’t aspirational fluff. It’s rigidly enforced. “If you begin to chip away at that, if you begin to sort of pump out some journalism which is a little bit second-rate, then you very quickly undermine your whole business model,” Slade says. The quality bar isn’t just high; it’s existential.

The pricing follows from this. A premium FT subscription runs about £600 annually, which Slade describes as “a reassuringly expensive brand”. The price isn’t just covering costs it’s signalling value. Exclusivity is part of the product.

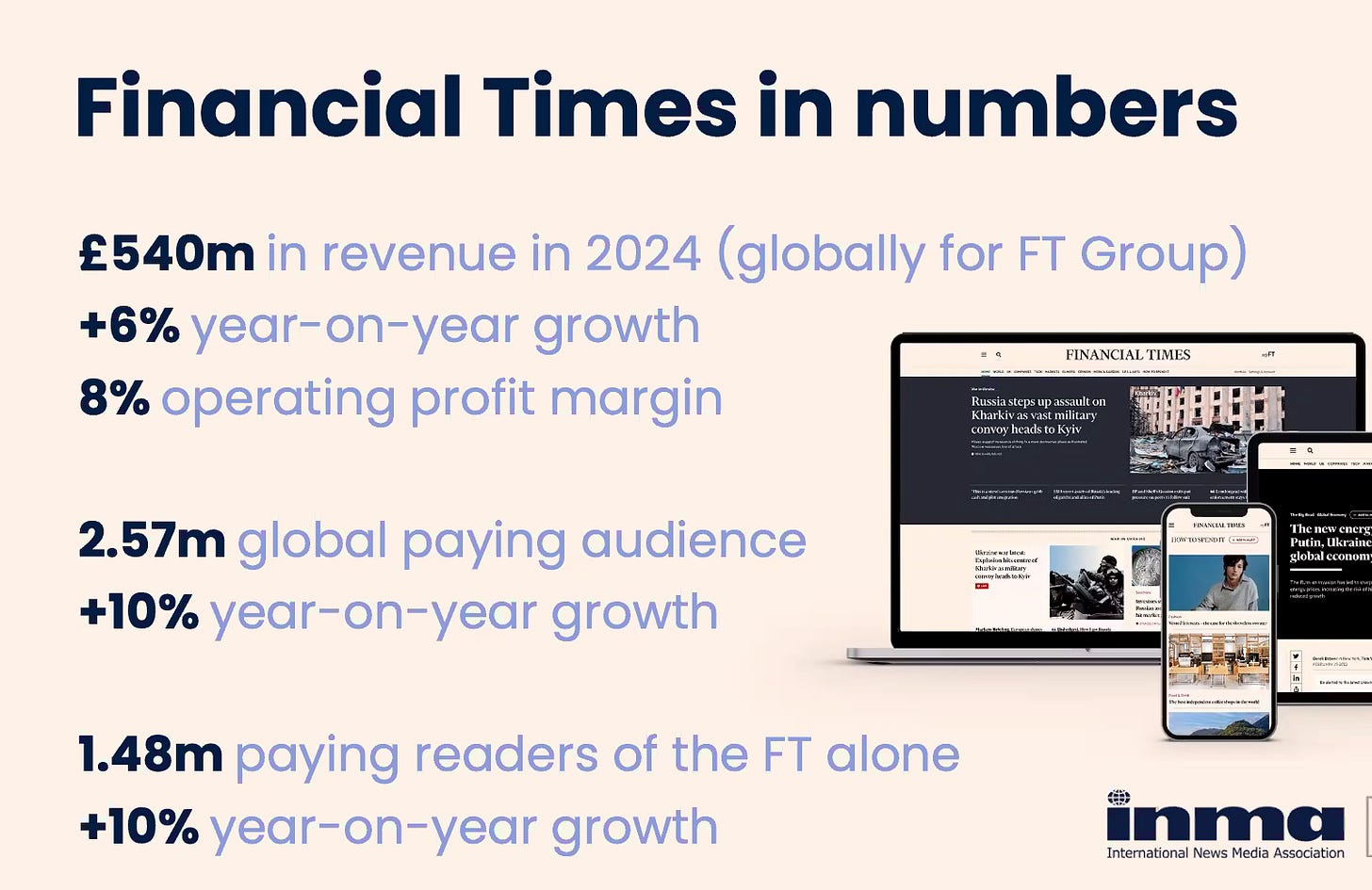

And it’s working. Revenue is up 6% with an 8% operating margin, achieved while social media referrals have halved and search traffic withers. These are the numbers keeping most publishers awake at night. The FT is having a rather good year.

Slade isn’t satisfied, though. He thinks they can charge even more.

The enterprise goldmine nobody talks about

Here’s a number worth dwelling on: the FT charges enterprise customers only 25% less than individual subscribers. Not 80%. Not 90%. Twenty-five percent.

About 70% of the FT’s engaged readers come through enterprise deals, which means the bulk of the business is priced at near-retail. The trick is borrowed from software companies: engagement-based pricing. Customers only pay for what they use, which aligns incentives beautifully. The FT actively wants subscribers to read the paper.

During the webinar, Piechota shares his own experience as an Oxford University subscriber: the FT’s team messaged him noting his reading habits lagged behind his colleagues and offered to help him get more from his subscription. It’s simultaneously helpful and mildly stalkerish—the five-star hotel approach to journalism.

For enterprise customers, the FT employs a dedicated success team that monitors usage and intervenes when accounts go dormant. It’s expensive, but the lifetime value of a corporate subscription justifies white-glove treatment. Unlike consumer subscriptions—which are a one-to-many marketing exercise—enterprise sales are one-to-one negotiations where personal relationships matter.

Slade reckons there’s further room to run. The newspaper is exploring a membership model that would sit above subscriptions—exclusive communities around topics like asset management or luxury, priced at £2,000 to £10,000 annually. Whether enough people will pay that much for the privilege of networking with other FT readers is unclear, but the margin for error is wide when you’re starting from a £600 baseline.

There’s also a quiet side business in what Slade calls “machine-read licences”. Consultancies, law firms, and financial services firms can buy feeds of FT content to plug into their own AI models. Even if consumer subscriptions face pressure from AI summarisation, the FT can sell the raw material to businesses building their own tools.

Nerds wanted

The idea to make the FT free for under-18s came from a schoolboy on work experience. He was sixteen. Slade and his team listened, found a corporate sponsor, and launched it. Now any student whose school registers can read as much FT journalism as they like.

It’s the kind of long-term thinking that quarterly earnings reports tend to strangle. The payoff, if it comes, arrives in a decade when some of those students start proper jobs. Or it won’t, and the newspaper will have spent years giving away its product. Slade seems comfortable with that uncertainty.

The FT has also hired its first full-time explainer editor to create visual, practical journalism for younger readers. But at a recent company town hall, the editor announced the recruitment strategy bluntly: “What we want is nerds.”

The FT experiments on TikTok but refuses to pretend to be cool. “We do not want to pretend that we’re all kind of cool and crazy,” as Slade puts it. Better to be honest about what you are than to fake relevance badly.

There’s a curious research finding here. The FT ran focus groups and discovered younger readers consume articles in reverse: headline first, then straight to comments, and only then—if it still seems worthwhile—the article itself. This would horrify most editors. Slade takes it as validation that community matters. The comments aren’t decorative; they’re part of the product.

Control as strategy

The FT has developed what amounts to a paranoid checklist for any distribution deal. Do we control the price?

Do we control the rights?

Can we see who’s using our content?

Do we own the distribution channel?

The newspaper wants all four. The logic is brutally simple: if your journalism is everywhere and free, you have no business. “If you’re letting anybody come onto your website and do whatever they want with your journalism, then you have no scarcity,” Slade says. “You have no control of price or rights or transparency or distribution.”

This philosophy shapes everything from the metered paywall to which AI companies can crawl the site. The FT has walked away from licensing deals where terms weren’t acceptable. It’s a publisher that actually says no, which is rarer in this industry than it should be.

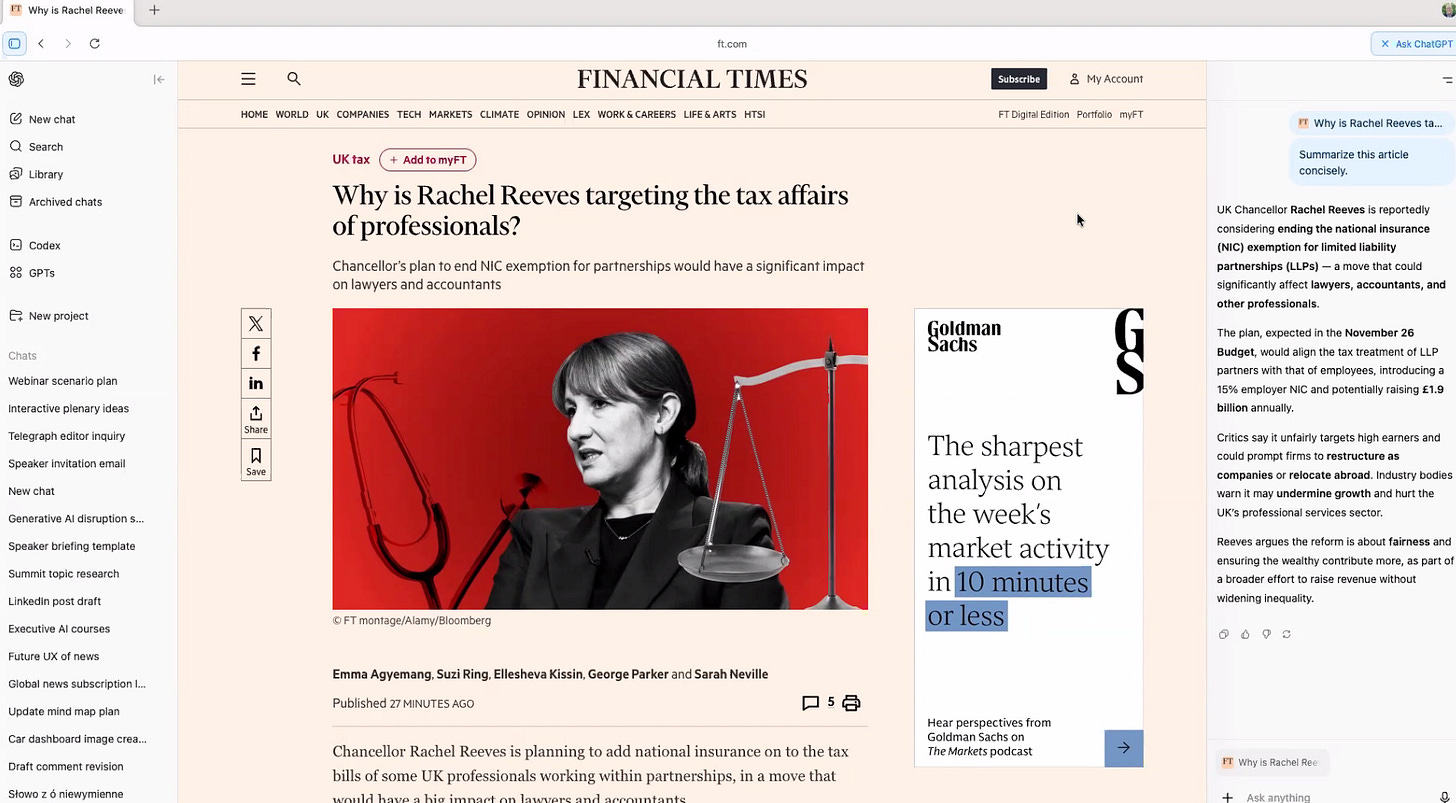

The FT does have a deal with OpenAI—Slade is cagey about details that permits crawling for “specific purposes” whilst retaining the right to object if OpenAI strays beyond agreed terms. During the webinar, someone shows him OpenAI’s new browser summarising FT articles. Slade doesn’t panic. The tool is using the questioner’s legitimate subscription. His concern is whether that summary then becomes training data and, crucially, who’s liable if the AI gets something wrong.

“If the summary had said the chancellor has no plans to end the NIC exemption for partnerships, and that would be a misrepresentation of what we’ve written,” he notes, referring to a recent article about UK tax policy, “we would then have the opportunity, through a licence, to say you have misrepresented that.” It’s about control, always control.

The optimistic case for AI licensing goes like this: it’s a circular economy. AI companies want good tools, good tools need reliable journalism, reliable journalism needs proper compensation. Everyone wins.

The pessimistic case: why would tech companies voluntarily pay when they can scrape everything for free?

Slade acknowledges some “may need regulatory intervention” but believes market forces will ultimately prevail. It’s a bet that enlightened self-interest beats piracy, which seems optimistic given the past two decades of digital media. Still, the FT is participating in licensing deals to help shape the market rather than watching from the sidelines as others set standards. Better to be inside the tent than outside it, even if the tent might be on fire.

Beyond AI

Ask Slade about artificial intelligence and he pivots immediately to broader disruptions. Changing reading habits. The collapse of trust in institutions. YouTube’s explosive growth as a distribution channel.

“We don’t say AI is the thing we need to get our heads around,” he explains. “Disruption is the thing we need to get our heads around, of which AI is a significant subcomponent.”

This is more useful framing than most publishers manage. Yes, AI matters. But so does the fact that teenagers now get their news from opinion podcasts. “I say, Well, that’s interesting, because that redefines news as opinion,” Slade notes. “And I would say opinion is a subset of news. I wouldn’t say news, it’s not the other way around. But increasingly, I think younger people are telling us that.”

View of FT on Chat GPT browser, Atlas

The FT collects birth years from all subscribers now, which allows segmentation by age cohort. Combined with qualitative research—actually sitting in rooms with younger readers and asking what they think news is—it builds a picture of how consumption is fragmenting.

Knowing the problem and solving it are different challenges, of course. But at least the FT is asking the right questions.

Value over volume

The FT keeps about 1.6 million subscribers to its flagship publication whilst competitors chase mass-market scale with heavy discounting. Slade frames this as “a balance” between volume and value, but his preferences are obvious.

A loyal subscriber accepts price rises, buys additional products, attends conferences. Compare that with the churn factory of aggressive discounting, where customers flee at the first renewal price. The economics aren’t even close.

There’s also a philosophical dimension that Slade articulates well. He watches journalists labour over every word, every punctuation mark. “If you’re putting that much effort and experience in, it should be justly rewarded. Chasing volume through huge discounting does no justice to that process.”

It’s admirable. It’s also not particularly actionable for most publishers. The FT can afford to be precious about pricing because its readers need the paper professionally. General news publishers don’t have that luxury. Their journalism might be valuable to democracy but it’s not valuable to individual readers’ monthly budgets. You can’t eat civic virtue.

What might actually work elsewhere

Infrastructure matters more than most publishers admit. When Slade ran both advertising and subscriptions as Chief Commercial Officer, he killed pre-roll video ads because they hurt subscription conversions. Viewers bounced when they saw them. Having both revenue streams under one boss made the trade-off simple: short-term ad revenue or long-term subscriber value? The reader won.

This structural decision—centralising commercial leadership—let the FT move faster than competitors where ad and subscription teams fight territorial battles. “It meant that we could move quicker in prioritising the customer,” Slade notes.

The reader-first principle extends to the website itself. The FT doesn’t burden pages with dozens of tracking cookies from ad-tech companies. Slade recalls checking competitor sites and seeing 120 cookies firing. The FT had six, three of them its own analytics. This isn’t altruism—it’s recognising that readers who feel surveilled by advertisers don’t subscribe.

Customer service gets similar investment. The FT pays for knowledgeable staff who actually read the paper rather than outsourcing to the cheapest call centre available. Again, the economics work because high subscription prices justify the cost.

So what travels beyond the FT’s specific circumstances? A few things, perhaps.

Don’t discount yourself into oblivion. The race to the bottom rarely ends well. If your journalism has value, charge for it properly and accept a smaller audience.

Reader relationships matter more than reader acquisition. The cheapest customer to keep is the one you already have. Invest in retention, not just conversion.

Control your distribution rather than renting someone else’s. Platforms will always prioritise their interests over yours. Build direct relationships however you can.

Be honest about what you are. The FT’s refusal to pretend it’s something cooler or younger might seem like a limitation, but it’s actually liberating. Readers can smell desperation.

None of this guarantees success. The FT spent twenty years building its model in an era when failure was still survivable. Most publishers are fighting for their lives now and don’t have two decades to experiment.

But the most important lesson is one Slade doesn’t quite say explicitly: the FT has been ruthlessly consistent about what it values. Quality over quantity, every time. Readers over advertisers, even when it hurts. Control over convenience, always. Long-term relationships over short-term growth.

It’s boring, really. No silver bullets. No clever hacks. Just discipline compounded over two decades until it becomes something that looks like success.

On the webinar, a question comes in about protecting content from AI crawlers. Slade’s answer reveals his frustration: “I am quite resentful, if I’m honest, of the cost that we have to incur in order to do that. I suppose, just as any shopkeeper would feel resentful about the need to have security guards.”

He shouldn’t have to spend money protecting journalism from theft when he’d rather spend it on producing more journalism. But there we are. That’s the business he’s in.

It’s an honest answer from someone who’s spent twenty years working out how to make quality journalism sustainable. Not solved, mind you. Just sustainable. For now. In one specific context that probably doesn’t transfer to most of the industry.

Which might be the most realistic assessment of where publishing stands that you’ll hear from anyone actually running a successful newspaper.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end of the article! This post is public so feel free to share it, and if you have not done so already sign up and become a member.